Innovation as an Imperative for the Mexican Oil Industry Post Energy Reform

Table of Contents

Author(s)

Javier Martínez-Romero

Visiting Scholar, Mexico CenterTo access the full paper, download the PDF on the left-hand sidebar.

Introduction

Mexico is among the developing countries that have progressively adopted policies toward a more liberalized and market-oriented economy. Throughout this process, which began in the 1980s, there have been various periods of aggressive privatization of previously government-owned companies. However, in spite of this wave of economic liberalization over the past 30-plus years, it had been very difficult to reach a political agreement to change the monopolistic conditions that prevailed in the energy sector. That changed in 2013 and 2014, when a major structural reform was accomplished in that sector in Mexico. Following that constitutional and legislative achievement, in July 2015 Mexico carried out a first round of oil block bids, beginning the implementation of the energy reform and signaling that the long-awaited opening of the country's oil industry to private and foreign companies had arrived (El Economista 2015a; Foros Milenio 2015). Although not all the oil fields included in that bidding process were awarded—only two of them were sold—the first round of auctions turned out to be very symbolic (El Economista 2015b). To be sure, this did not mean that private or foreign companies were absent from Mexico prior to 2015; the difference is that companies other than Pemex, the national oil company, can now engage in the business of exploration and exploitation, activities that Pemex had previously monopolized under Mexican law.

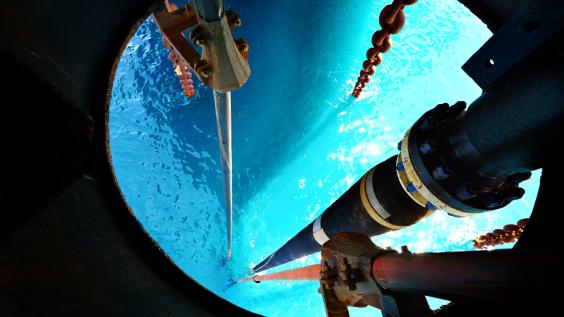

A recurring argument put forth by the Mexican government to galvanize support for the energy reform was that Pemex lacked the appropriate technology to exploit deepwater oil reserves (Presidencia de la República 2016). This fatal flaw, coupled with the weak financial position of the state-owned company (mostly due to an excessive tax and royalty burden), prevented Pemex from investing in technological research. Thus, the entry of foreign companies was justified on the grounds that opening the energy sector would result in greater technological competence and financial capacity, because these companies would immediately bring their own technological prowess to bear on Mexican oil production. According to Mexican authorities, not only would these major oil companies provide modern technology to tap into deepwater reserves, but by means of collaborative agreements, Pemex and other local organizations would also have the opportunity to upgrade their own technological capabilities. The promise was essentially one of technological transfers.

Some critics of the reform argue that breaking up Pemex’s monopoly was not necessary to acquire the technology that the country’s energy sector required, since the company in any event had always relied on foreign technology for most of its operations (Domínguez 2008). Others believe that Pemex’s financial problems are an obstacle to acquiring technologies that would require enormous amounts of investment and time to assimilate (Miranda 2009). This last line of reasoning stresses that breaking up Pemex’s monopoly on the Mexican oil industry will result in enormous gains in productive efficiency and aid the longer-term financial health of the country as a whole. Assessing whether or not this is the case is outside the scope of this paper. This study focuses instead on the technology transfer argument made by the Peña administration and on an issue neglected in much of the subsequent discussion: technological innovation.

It cannot be denied that in the last decades the oil industry has experienced enormous changes in the way innovation is taking place, altering the ways in which companies participate in the industry landscape, among other effects. Under these more dynamic innovation conditions, a few countries, such as Brazil, have achieved what some authors have called “technological catching up.” What this means is these countries now participate in the overall innovation efforts of this global industry in a meaningful way (Maleki and Rosiello 2014). The catching-up concept, first used in economics by Abramovitz (1986) to explain the gap reduction in economic output, has been applied in evolutionary studies of technological change to explain how some countries—especially newly industrialized Asian countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore—have progressed from the initial adoption of foreign technology transfers to an innovation phase, in which local improvements over that technology are a reality and innovation has become second nature (see, for example, Soete 1988; Shin 2013).

For instance, it is well known that Petrobras, the Brazilian national oil company, has increased its economic performance dramatically thanks to its innovation efforts in deepwater, among other factors. Accounts of the Brazilian catch-up show the importance of the existence of an innovation system systematically fostered by the country itself, which means that different agents with different capabilities interact under policies oriented toward promoting technological learning (Dantas and Bell 2011). Thus, in a world in which oil may be harder and harder to reach, the performance of national industries depends not just on adapting and mastering foreign technology, but also on developing domestic innovative solutions, nurtured by the systematic incentivizing of an innovation culture.